Between two cathedrals

A wander around central Ōsaka

Kyōto, the old capital of Japan, packed with temples, is, although increasingly also packed with tourists, a place where the veil between the worlds feels thin, whether angels or devils are on the other side. Ōsaka, on the other hand, 40 km down the Yodo River, is seen as the epitome of a brash, modern city. This is not a new development either, as it was always Japan’s commercial capital, where locals are said to greet each other with “How’s profit?” It may be thought of as devoid of “enchantment,” to use a term currently popular among Christian writers, but that is what I went looking for in today’s stroll through the centre.

The area around the Catholic cathedral is Tamatsukuri, and on leaving Tamatsukuri station one of the first things I saw was a replica of Michelangelo’s statue of David. I could find no explanation, but it seemed an auspicious start to a Christian-history-and-culture walk.

On the way to the cathedral I passed Tamatsukuri Jinja (a jinja is a Shintō temple), which is said to date from 12 BC, deep in prehistory. “Tamatsukuri” means “jewel-making,” and in ancient times this area was a centre for making magatama (“curved jewels”), which are comma-shaped jade artefacts that had a ceremonial purpose at the dawn of Japanese history. One of the Three Sacred Items of the monarchy is a magatama, the others being a sword and a mirror. Before the first proper capital was built at Nara, 28 km to the east, in 710, the imperial palace was moved around every few years, and it was in Tamatsukuri from 645 to 655.

Ōsaka remained an important town, the nearest seaport to Nara and Kyōto, and voyages to China set off from here during the Tang Dynasty (610–907). Monks went to study Buddhism in Chang’an, the Chinese capital, where they would have come into contact with Nestorian Christianity, and it is sometimes argued that the schools they founded, notably Shingon Buddhism, founded by Kūkai (774–835), show Christian influence. It is even possible that there is a direct Christian connection, as Christians may have visited Japan, although this idea has now been largely rejected.

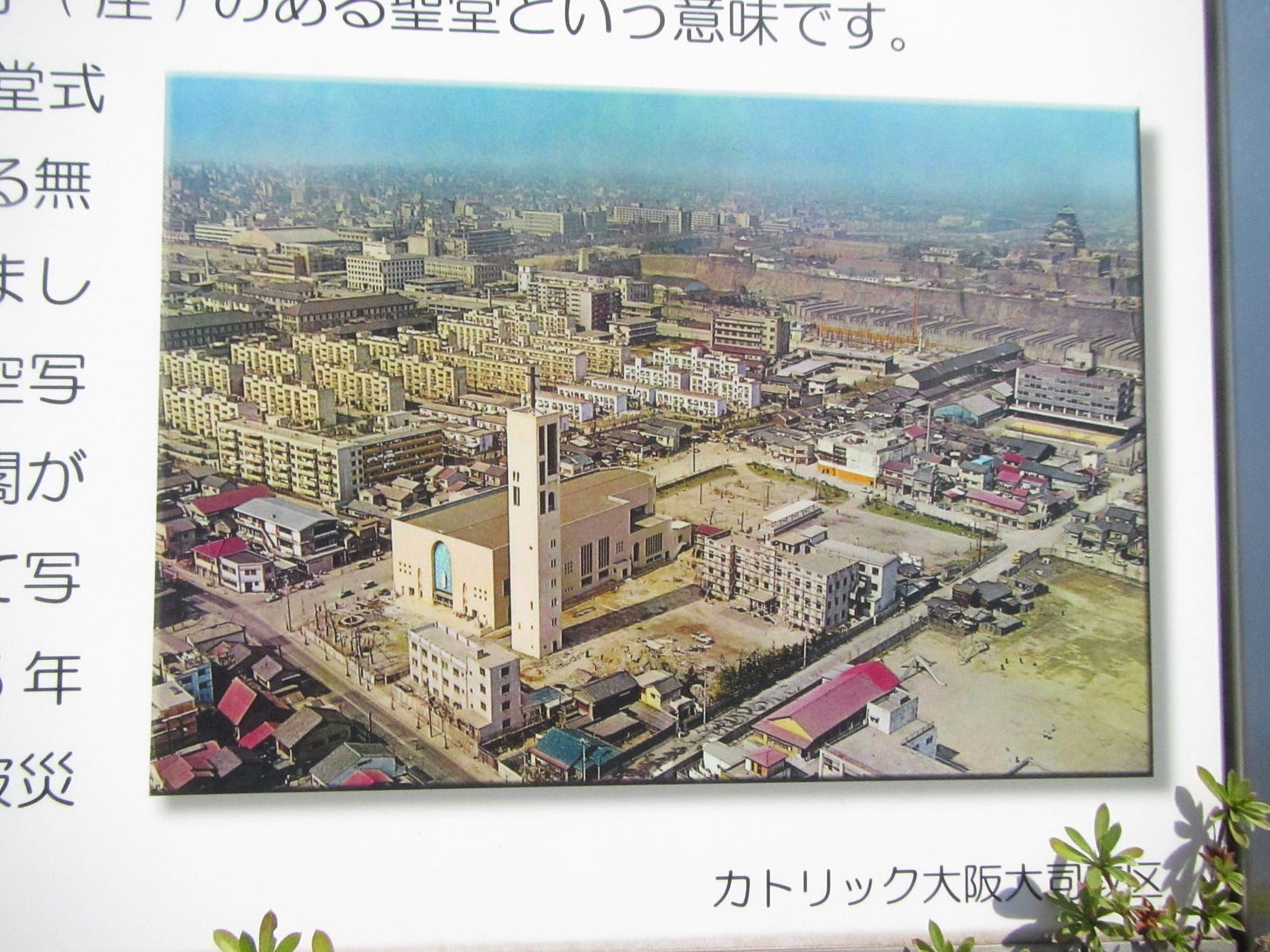

St. Mary’s Cathedral, the seat of the Archdiocese of Ōsaka, is a Modernist building, built in 1963 on the site of an 1894 building destroyed by the bombing in 1945. Designed by Hasebe Eikichi (1885–1960), it won several awards, but makes me think of a Costco. To my mind, the only feature of architectural interest is the large recessed area on the outside, above the front door, which includes a marble statue of the Immaculate Conception, and is covered with sky-blue taizan tiles, and decorated with stars. The cathedral had a bell-tower, but that was demolished after the earthquake of 1995.

Front of the cathedral

Recessed area

Information board showing the cathedral when newly built, complete with bell-tower

In previous articles I have written about Takayama Ukon (1552–1615), Baron of Takatsuki, between Ōsaka and Kyōto, who, for being Christian, was demoted to the rank of retainer, and finally exiled, dying of a tropical fever not long after arrival in Manila. He was beatified in 2017, and inside the cathedral a chapel is dedicated to him, with his relics, as part of the campaign for canonisation.

Another Christian aristocrat of the same era was Hosokawa Garasha (1563–1600). Born Akechi Tamako, at 16 she married Hosokawa Tadaoki (1563–1646), but in 1582 her father Akechi Mitsuhide (1528–1582) betrayed and killed Oda Nobunaga (1534–1582), the first of the three great unifiers of Japan after more than a century of chaos, making Tamako a traitor’s daughter. Her marriage seems to have been genuinely affectionate, as her husband refused to divorce her, and instead sent her to a mountain village, and the second unifier, Toyotomi Hideyoshi (1537–1598), later relented and allowed Tadaoki to bring her to Ōsaka on condition that she remain confined to his mansion. Her lady-in-waiting, Kiyohara Maria, a Christian whose husband was a friend of Takayama Ukon, told Tamako about the faith, and she surreptitiously visited the Ōsaka church in 1587. In that year, Hideyoshi introduced the first anti-Christian measures, so Tamako was immediately baptised in private by Maria, as “Gracia”, of which “Garasha” is a Japanisation. She learnt Latin and Portuguese, and was fascinated by St. Thomas à Kempis’s Imitation of Christ.

In 1595, Tadaoki’s life was briefly in danger, and he told Garasha to kill herself if he were killed, but the priests insisted that she must not commit suicide under any circumstances. In the power vacuum after the death of Hideyoshi in 1598, Tokugawa Ieyasu (1543–1616), the last great unifier, marched east with a large army, including Tadaoki. Tokugawa’s main rival, Ishida Mitsunari (1559–1600), captured Ōsaka Castle, which Hideyoshi had just built, planning to take as hostages the barons’ families from their nearby mansions, to force the barons to change sides. Garasha was instructed by a retainer to kill herself, to prevent use as a hostage and because of the possibility of rape, but she refused, and he then killed her, set fire to the mansion, and performed seppuku. Garasha’s refusal to follow the samurai code of honour is sometimes viewed as a form of martyrdom.

Ishida’s actions had the opposite effect to that intended, as disgust at his treachery pushed wavering barons onto Tokugawa Ieyasu’s side, leading to his overwhelming victory at the Battle of Sekigahara in 1600, and formal appointment as Shōgun in 1603, after which the Tokugawa family remained in power until 1868. However, this was not favourable for Christians, as Tokugawa increased the severity of the anti-Christian laws, culminating in outright prohibition in 1614.

An odd coincidence is that the cathedral was built adjacent to and overlapping with the site of the Hosokawa mansion. Perhaps for this reason, the cathedral is dominated by memorials to Takayama Ukon and Hosokawa Garasha.

The cathedral’s architecture may not be impressive, but its artwork is. At the front, to either side of the sky-blue recessed area, there are stone statues of Takayama and Hosokawa by the Japanese sculptor Abe Masayoshi (born 1966). Inside there are numerous paintings of events in Takayama’s life, many in a rather naïve style, perhaps by local amateurs. There are wooden statues of the crucified Christ, flanked by the Virgin Mary and St. John, and the 14 stations of the cross, St. Francis Xavier, and St. Agnes. There are 100 stained-glass windows by Habuchi Kōshu (1902–1971), showing the life of the Virgin Mary, St. Francis Xavier, and the birth and baptism of Christ. There are also paintings of the 26 martyrs of 1597, on hanging scrolls similar to those used for paintings of Buddhist monks.

Takayama Ukon

Hosokawa Garasha

The masterpieces, however, are the works of the Kyōto-born Dōmoto Inshō (1891–1975), widely accepted as the greatest Nihonga artist, and the cathedral is worth a visit for these alone. Behind the altar there is a huge painting of the Virgin Mary in glory, flanked by Takayama and Hosokawa, and there are smaller individual paintings to either side showing Hosokawa in prayer immediately before her murder, and Takayama on arrival in Manila. In the late 19th century, Japanese art was regarded with contempt, and might have died out had it not been for the US art critic and Buddhist convert Ernest Fenollosa (1853–1908), who helped to develop Nihonga, the movement, continuing today, that combines the various traditional Japanese schools. Although Dōmoto did about 600 paintings commissioned by Buddhist temples, mainly in Kyōto, he was not Buddhist, but was fascinated by religion, and produced numerous Shintō, Hindu and Christian works. Christian Nihonga is unusual, and Dōmoto’s Virgin in Glory is extraordinary, being painted on gold leaf, following the 17th-century Rinpa school.

Unfortunately, there is a sign saying that photographs of the artwork must not be distributed. I have posted an overall view, which might be acceptable, but not close-up photographs.

Immediately behind the cathedral, on the site of the Hosokawa mansion, there is a small park, Ecchū Park, named after one of Hosokawa’s titles, and across the street there is Ecchū Well, which is all that was left after the mansion burnt down. In 1934, local residents erected a stone monument in Garasha’s honour, carved with her last words. In my first article I mentioned what I thought was Japan’s only Christian holy well, but this could be seen as a second, although the little shrine next to it is Buddhist.

Ecchū Park

Ecchū Well

The well, monument and shrine

A short distance northwards I reached the outer moat of Ōsaka Castle. The cherry blossom season was coming to an end, but lots of people were still eating and drinking on mats. Almost nothing remains of the castle Hosokawa knew, as it was completely rebuilt in the 1620s. The keep then burnt down after being struck by lightning in 1660, and most of the other buildings were destroyed in fighting in 1868 and the bombing in 1945. The present keep is a ferroconcrete replica (only 12 Japanese castles have the original keep), but visitors don’t seem to mind. The only 17th-century buildings are two of the turrets on the walls.

One of the two 17th-century turrets, with the keep in the distance

The ferroconcrete keep, with a zoom

Outside the castle grounds

I didn’t pay to go into the castle, but walked north along the moat, and was soon at the river, a distributary of the Yodo River. I noticed a cross on a building across the river, and my map showed it to be the Seventh Day Adventist Church.

The Seventh Day Adventist Church across the river

The river divides to either side of Nakanoshima (“Middle Island”), which is the administrative centre.

The rest of my walk was a 4-km stroll downriver, visiting all three of central Ōsaka’s surviving pre-war churches. Strolling through the concrete, it’s fascinating to see the occasional red-brick bank or office building that survived the bombing, and churches stand out in being neo-Gothic whereas commercial buildings of that era are neo-Classical.

A bombing survivor

Another, with an Art Deco doorway

The first church was Naniwa Church, of the United Church of Christ in Japan (UCCJ). Built in 1930, I found it a rather dull neo-Gothic building, but it was designed by the US architect William Merrill Vories (1880–1964), who I’ve mentioned in other articles. He designed dozens of churches, so that my first thought on seeing a pre-war Protestant church is that it must be his. Besides his architecture firm, he started his own drug company, and became extremely rich, but lived a modest lifestyle, using his wealth to fund hospitals and missionary work. In 1941, he took Japanese citizenship, adopting his wife’s surname, and he was involved in the surrender in 1945; it was he who recommended that the Emperor renounce claims of divinity.

Naniwa Church, next to another bombing survivor

The UCCJ was created in 1941, when the government forced all Protestant denominations to merge into one patriotic church, and most remained merged when allowed to separate again after 1945. Naniwa Church was originally Congregationalist, founded with 11 members in 1877, and is said to have been Japan’s first church to run without overseas funding. The interior has fine, dark-timber panelling, attractive in a sombre sort of way, looking very much how I, being northern English, think of Nonconformist “chapels”; I remember hearing Anglicans mock “pitch-pine piety”.

Inside Naniwa Church

The second church was the UCCJ’s Ōsaka Church, built in 1922, and also designed by Vories, which I found much more attractive than Naniwa Church. Neo-Romanesque and mellow brick, with ornate details in the brickwork, the façade looks like a church in a crowded Spanish or Italian city. At one side, the narrow garden with an Italianate tower at the end gives the feeling of a convent. This church also used to be Congregationalist, and was founded by US missionaries in the 1870s.

Ōsaka Church

Getting now into the port district, there was the last church; the Anglican cathedral, Kawaguchi Christ Church. Built in 1920, and designed by the US mission architect William Wilson, it is the oldest extant church in Ōsaka. To English eyes, it is a rather dull, red-brick parish church, but the interior is more attractive; the mellow brick and Romanesque design makes it look much older, putting me in mind of an Italian village church. On one wall there are stained-glass windows in the style of botanical drawings, made in 1993 by Suzuki Chikako, showing fruits and other plants mentioned in the Bible. The church, founded in 1870, was the first church in the Ōsaka area. That was before legalisation of Christianity in 1873, so it mainly served foreigners.